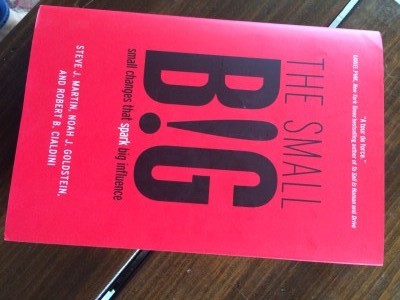

Influencing people and decisions is complex, but there’s much we can learn from persuasion scientists. This past weekend I read the great new book, The Small Big: Small Changes That Spark Big Influence, by Steve Martin, Noah Goldstein and Robert Cialdini.

Here are some highlights, all based on fascinating research studies that the authors explain in the book.

Influencing people and decisions is complex, but there’s much we can learn from persuasion scientists. This past weekend I read the great new book, The Small Big: Small Changes That Spark Big Influence, by Steve Martin, Noah Goldstein and Robert Cialdini.

Here are some highlights, all based on fascinating research studies that the authors explain in the book.

Communicating

- Before a meeting or interview, write about a time you felt powerful and/or adopt a high-power physical posture. “High power” people are more persuasive.

- Make sure to present your credentials before trying to influence a group. Authorities’ opinions dominate people’s minds, shutting down cognitive consideration of other factors.

- Focus first on the possibilities and potential of your proposal, as potential arouses more interest than realities. Once the attention is focused on the potential, provide supporting information about the benefits, e.g., testimonial, research data.

- Admit uncertainty vs. convey over-confidence. A person’s expertise, when coupled with a level of uncertainty, arouses intrigue. As a result -- and assuming the arguments that the expert makes are still reasonably strong -- this drawing in of an audience can actually lead to more effective persuasion.

- Similarly, consider using a list of “worst practices” instead of “best practices.” People pay attention to and learn from negative information far more than positive information. Also, downside information is more memorable and is typically given more weight in decision-making.

Influencing Decisions

- Ask people to choose between two options vs. offering just one. Then influence them to opt for your preferred option by pointing out what could be lost if they don’t select that option.

- Similarly, people make decisions based on context and comparisons. By first presenting an option that people think is a bit too costly, or one that they might think will take to much time, you can achieve the desired impact of making the target proposal seem even more like the “Goldilocks proposal that it is – just right.

- Determine whether you’re trying to get buy-in or follow-through. If it’s getting people on board, make the sequence of steps as flexible as practical and emphasize that flexibility when announcing the initiative. If the bigger issue is execution, give the rollout sequence a very structured order and emphasize how, once in place, the program will proceed in a straightforward, uncomplicated fashion.

Forming Relationships

- Explicitly use someone’s first name more often when seeking to influence them.

- Identify uncommon commonalities between you and another person, fulfilling people’s desire to both fit and still stand out.

- When meeting someone for the first time dress at a level that matches your true expertise and credentials. This is in keeping with a fundamental principle of persuasion science – authority. Authority is the principle that influences people, especially when they are uncertain, to follow the advice and recommendations of those they perceive to have greater knowledge and trustworthiness.

Getting Commitments

- Remind people of the significance and meaningfulness of their jobs, and show how what you’re asking them to do is related to that meaning.

- To get people to follow through on promises, e.g. I’ll bring up your idea in the executive staff meeting, ask how they’ll go about accomplishing the promise they’ve given to you. This specificity helps them follow through.

- If you believe that you will encounter resistance with your requests for an immediate behavior change, you might be more successful if you instead ask for a commitment to change at a given time in the future, say three months from know.

- Appeal to people’s sense of moral responsibility to the future version of themselves.

Meetings

- Ask people to submit information before a meeting. This often increases the number of voices that are heard, potentially leading to a greater number of ideas generated. Similarly, ask people to spend a few moments quietly reflecting on their ideas, writing them don, and submitting them to the group. Doing this can help ensure that any potentially insightful ideas from quieter members won’t get crowded out by people with louder voices.

- The person who leads the meeting always speaks last. If a leader, manager or family elder contributes an idea first, group members often unwittingly follow suit, leading to alternative ideas and insights being lost.

- If you want to create an atmosphere of collaboration and cooperation, have people sit in a circular seating arrangement.

- Creative sessions are often more fruitful when held in rooms with high ceilings.

Building your network

- Just ask! People tend to underestimate the likelihood that a request for help will result in a yes. Plus, those who can help often don't offer because they wrongly assume their help isn't needed. Why? Simply because it wasn’t asked for.

- People who help others but don’t ask for favors in return are much less productive than their colleagues. The way to optimize the giving process in the workplace is to arrange for exchange: a) be the first to give favors, offer information or provide service, and b) be sure to verbally position your favor, information or service as part of a natural and equitable reciprocal arrangement. (“I was happy to help. I know that if the situation were ever reversed, you’d do the same for me.”)

- Provide explicit thanks and genuinely communicate your appreciation for the favors done and the efforts made on your behalf.